The questions of what to teach and how to teach are applicable to every course. Calculus is no exception. This preface tries to answer these two questions, based on the principles of RUM and GUT, where (i) RUM is Relevant, Useful, and Modern, and (ii) GUT means to Go to daily life motivations, Use modern computers, and Tell calculus stories.

Calculus scares many high school and college students. Most people learn calculus because their study programs require the course. Mathematical Association of America (MAA) in 2015 reported that math is the “most significant barrier” to entering or finishing a program in STEM fields. Here, STEM stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Students cannot pass the barrier due to a very high failing rate. For example, the Calculus I failing rate at DFW grades is as high as 27%, according to an MAA study. The widespread calculus fear among students is real!

Even if they successfully passed their calculus courses, ten or twenty years later, few people ever remember what the calculus method is for. Have they ever used calculus in their work or life? It is not uncommon that calculus becomes a topic of party jokes. Sadly, for many people, calculus is simply an exemplary subject of popular jokes on college courses of “completely right, but totally useless.” Even worse, some people hate calculus after taking the course, and of course, spread their calculus hatred to their family, friends, and peers. Some American politicians and corporation managers deliberately, or even proudly, announce to the public their bad performance in calculus classes, while none of them would wish to show their ignorance of history or the English language. Why? Logically, the only reason is that what they learned in their calculus classes was truly useless in their career. Therefore, ignorance of calculus shows no stupidity, while good-at-calculus may show eccentricity. A typical engineering major would take at least 12 units of calculus in Calculus I, II, and III series, which is about 10% requirement of his total graduation units. Students must feel awful when being told by their potential job managers that one of their most challenging college courses is useless!

Therefore, calculus education must be modernized so that students can use it in their advanced courses, careers, and daily life, particularly in today’s digital economy. Our data-based interactive calculus attempts to make the moderniza- tion. The main features of this book include interactive, visualization, data-based, the minimized requirement of algebra and trigonometry (we review the required algebra and trigonometry in a box where needed), and learning-by-doing. Another distinguished feature is our fast pace, which synchronizes with Physics I and II. For example, the basic ideas and applications of Green’s theorem, Stokes’s theorem, and the divergence theorem are explained in the first semester, while the traditional calculus does not explain these theorems until the end of the third semester, after Physics I and II. The third distinguished feature is the inclusion of modern mate- rials, such as Stokes-Cartan theorem, fast Fourier transform (FFT), n-dimensional (nD) integrals, Monte-Carlo simulation, and computer languages of Python and R.

Pedagogically, we adopt the methods of “repetition learning” and “learning by doing.” Numerous studies have shown that learning advances through repetition and practice. “Is it not a pleasure to study and constantly apply the lessons that you have learned?” said Confucius. In our book, each method, definition, or theorem is explained three to five times at different levels of mathematics with applications to physics, engineering, music, etc. For example, we relate calculus with the motion of a pendulum, the measurement of Earth’s mass and gravitational constant g, Faraday’s law for electricity generation, Ampere’s law for electric motors, heat radiation and sunlight on Earth’s surface, heat conduction and cooking, water waves in the ocean, sound waves in music, and electromagnetic (EM) waves for radios and mobile phones.

The first advantage of our book is thus to remediate the traditional calculus’s first and foremost defect of slow-pace and disjointness between calculus and calculus- based physics. For example, Physics I needs vectors for force balance in statics and derivatives of position vectors in kinetics for velocity and acceleration. However, the traditional calculus will not teach vectors until the beginning of Calculus III. The college-level calculus-based kinetics, gravitational potential, work and energy, and thermodynamics all need the concept of line integral, surface integral, and volume integral, but these materials are again not taught until the later part of Calculus III. Electromagnetism in Physics II uses the divergence theorem to help understand Gauss’s law when computing the electric field generated by the electric charge. Students can also use Green’s theorem or Stokes’ theorem to help under- stand Faraday’s law and power generation, when computing the electric current in a closed metal loop generated by moving a magnet in and out of the loop. The theorem can also help understand Ampere’s law and electric motor, which computing the rotational magnetic field generated by an electric current flowing through a wire. Professors of physics, engineering, and science are frustrated with the students’ lack of proper mathematics preparation on vectors, Green’s theorem, and the divergence theorem when teaching these physics topics. The accusation of their improper mathematics preparation is unfair on students. It is the design defect of a disjoint mathematics curriculum! Students have not learned these cal- culus methods before taking Physics I and II. Thus, physics professors have to teach these mathematical methods themselves, although they may not name these methods as mathematical theorems. Many students and instructors have never realized that Faraday’s law, Ampere’s law, and Gauss’s law can be expressed in the form of Green’s theorem and divergence theorem.

It is common that a massive 1,200-page calculus-based general physics text- book includes many pages of calculus. Students are frustrated with calculus-based physics because of “too much math.” Authors of the physics books often share their pedagogical ideas about the needed calculus in the following way. “We try to make calculus and other mathematical tools used in this book self-contained so that students do not need to go elsewhere for mathematical help.” Aha, does this statement bluntly say that “the calculus taught in the mathematics department has little use in our physics classes, and we have to teach our own calculus? ” A more disturbing fact is that the authors of physics textbooks do not even mention the words “divergence theorem” when teaching Gauss’ law for an electric field, or Stokes’ theorem when teaching Faraday’s law.

Our book provides sufficient mathematical skills to support the basic courses of undergraduate physics and engineering. For example, we followed the three Physics books by Fishbane et al. (2005), Knight (2018), and Serway and Jewett (2018). Some traditionally popular math concepts that are rarely used in physics and engineering courses are not included in this book, e.g., convergence of infinite series, trig-substitution, definition of continuity, and curve sketching using deriva- tives. Some existing calculus books go the extra mile to describe some uncommonly used physics laws or other applications, e.g., Kepler’s laws and their derivations and bi-normal moving coordinate frame on a 3D curve. We leave out these. Instead, we use the space to include more commonly used materials, e.g., Maxwell equa- tions, EM waves, Monte Carlo integration, Fourier series, FFT, spectrogram for time-frequency analysis, and random walk. These very useful materials have been left out in the traditional texts. Most of all, the traditional texts do not sufficiently use modern computing, data, and visualization as figures or animation.

What was overdone in the traditional calculus text? Limits, continuity, log differ- entiation, hand-graphing, optimization, areas, inverse functions, integration tech- niques, convergence of infinite series, Taylor series, curvature, binormal form, and too many formulas without the meaning of common sense, e.g., y = xx. We stream- line these materials using computers.

Why has it been so bad in calculus education? Has our calculus education failed in the last 50 or 70 years? The answer can be yes or no. No, if considering the dramatical progress in science, technology, and society in the last several decades. Calculus and other mathematical methods have provided effective support to the progress. Yes, if considering the waste of an enormous amount of time by the people who did not make use of calculus in their lives.

Can we do better in math education from now on? Do we need an overhaul in conventional math education? Can we make calculus more useful and relevant, such as better supporting physics and other advanced courses? How can students understand, remember, and use the fundamental ideas and methods of calculus? In the big data era, can calculus education incorporate modern computers and smartphones? Can we allow our students to enjoy calculus as they enjoy video games, movies, sports, and shopping? More concretely, can our calculus courses help students find paid summer internships? Can we have a lower failure rate com- parable to humanity classes? Overall, how can we modernize calculus education so that students can efficiently learn and use calculus?

When interviewed by the Khan Academy in 2013, Tesla Motors CEO Elon Musk partially answered the above questions. He called for an overhaul of the vaudevillian-style traditional education and suggested a more game-ify process of learning. He encouraged instructors to justify why students should learn these things so that students would not be puzzled about why they were there.

Indeed, Musk got the point: What do today’s students want to learn? How can they learn effectively? Today, more than two million Americans receive bachelor’s degrees each year, while in the 1950s the number was less than half a million, who were predominantly white elite males and had little concern about getting employ- ment after a bachelor’s degree. Today, calculus classes face a different population than 70 years ago. For different populations of students, calculus instructions must change to meet their needs. Now, the main purpose for most students to attend college is to get a decent job. If they find that calculus cannot help with their em- ployment, many of them may not take the course if not required. Hence, forcing students to take calculus because of requirements is a traditional system. Should the system be modernized so that students choose to take calculus for its usefulness in their jobs?

We believe that we should. The modernization may be a twofold problem: What to teach and how to teach. This book tries to solve this problem and provides a concrete way to support Musk’s answers.

“What to teach” is the issue of material selection. This book selects materials based on the RUM principle: Relevant, useful, and modern (Page et al. 2024). “How to teach” is the pedagogy issue. This book uses the GUT approach: Go to daily life motivations and historical origin of the ideas, Use modern computers to work out real-world problems, and Tell stories of the calculus ideas, methods, and applications. The English word “Gut” means a strong belief that does not have to be decided by logical reasoning. Our modern calculus encourages gut feeling and computer usage. It has a very fast pace and completes a round of all the fundamental theorems, concepts, and methods of calculus within the first semester. We can do so because we focus on the main purposes and methods of calculus.

The purpose of calculus is prediction. For example, you predict the cross-section area of your waist after you measure the location coordinates of your waist’s boundary perimeter using Green’s theorem. This example has apparently impor- tant medical applications for predicting the cross-section area of an organ while measuring only the boundary of the organ. The purpose of prediction is different from the traditional purpose statement that calculus is a study of change. Although this traditional “change” statement is not wrong, it limits students’ imagination for “prediction” applications and does not express the full power of calculus.

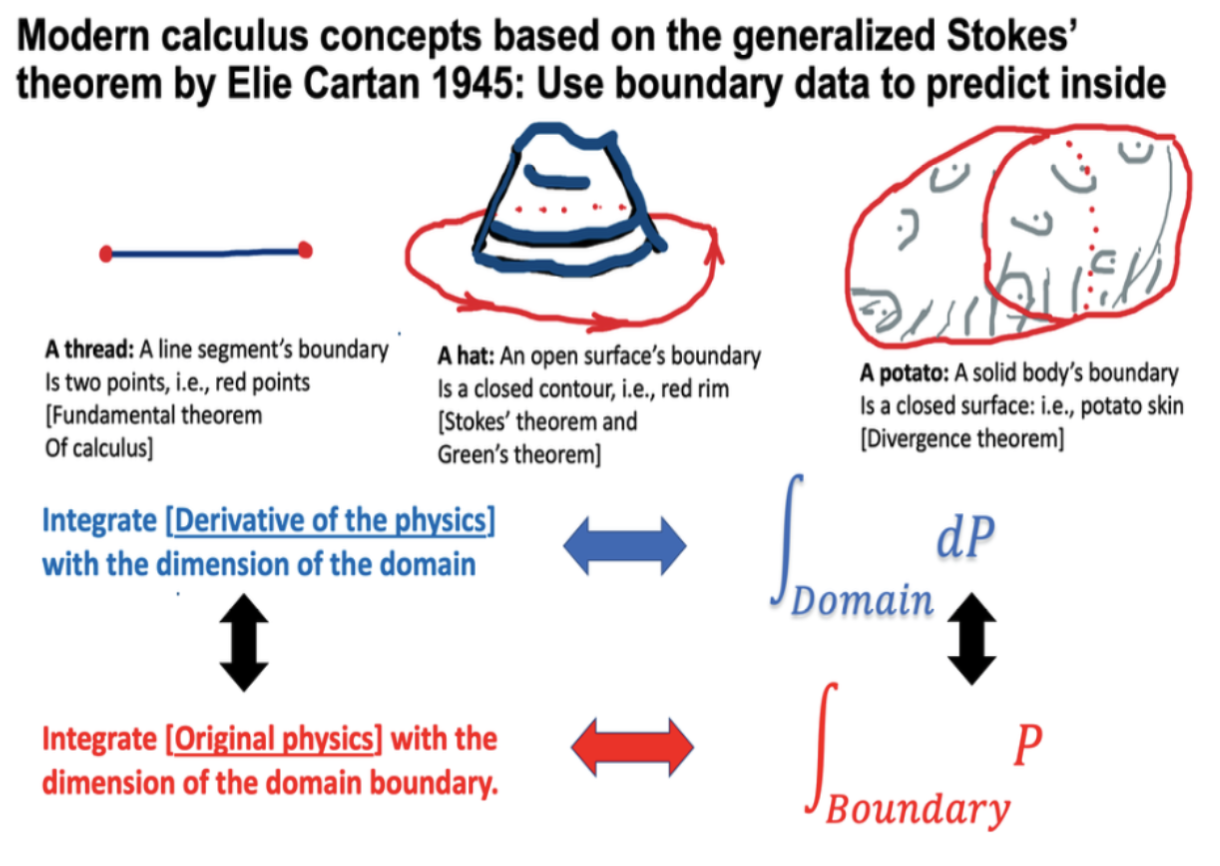

Following the ideas of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) and Élie Cartan (1869-1951), with few exceptions, all the geometric subjects in our 3-dimensional space may be classified as a curve, a surface, or a solid, as shown in Fig. 0.1. The boundary of an open curve is the two endpoints. The integral of a function on the curve can be predicted by the antiderivative’s data at the two endpoints: the boundary of the open curve.

This corresponds to Newton’s second law of motion and the fundamental theorem of calculus: an integration of force is equal to momentum differences between the two points.

The boundary of an open surface, such as a hat, is a closed curve, or called a closed contour. A relationship between an integration on the surface and another on the closed contour corresponds to Faraday’s law or Ampere’s law in electromagnetism. In calculus, this corresponds to Stokes’ theorem or Green’s theorem.

The boundary of a solid, such as a potato, is a closed surface, e.g., the potato skin. A relationship between an integration in the solid and another on the closed surface corresponds to Gauss’ law of electric field or magnetic field. In calculus, this corresponds to the divergence theorem.

We have chances to experience these physics laws at home, in classrooms, in labs, in museums, and in nature. We can also watch YouTube videos for these physical phenomena and their corresponding laws. In this way, students can understand how calculus is related to the fundamental laws of nature and how calculus models can be set up to solve practical problems. Instructors help students to perform computing in order to reach quantitative solutions for science, engineering, or social science applications.

The calculus method is “cutting-and-adding.” Cutting an object into smaller pieces is called differentiation, and adding all the small pieces together is called integra- tion. We use data and computer languages Python and R to quantitatively describe the small pieces and their accumulation, i.e., the differentials and integrals.

In the first semester (i.e., Interactive Calculus I or iCal I), we teach coordinates, vectors, computer graphics, the fundamental theorem of calculus, mean value the- orem, lines integral, surface integral, Green’s theorem, Stokes’ theorem, divergence theorem, probability density function, Monte Carlo integration, Fourier series, and power spectra. All of these are based on the same method of “cutting-and-adding.” We repeatedly teach this idea in 1-dimensional (1D), 2D, 3D, and nD spaces. We train students to draw diagrams of “cutting-and-adding,” formulate and compute the cuts (i.e., the differentials) and their quotients (i.e., derivatives), and add the differentials (i.e., integrals from adding). We leave tedious algebra and computing, such as partial fractions and the substitution by trigonometric functions, to comput- ers and modern software Apps, such as ChatGPT, R, and Python. More advanced topics, such as Newton’s method for solving nonlinear equations, formulation of the least-square fitting, time-frequency analysis, and the rigorous proofs of Taylor’s theorem and Stokes’ theorem, are deferred to Interactive Cal II or III (i.e., iCal II and III), where all the aforementioned theorems will be taught again and again, for at least three more times with application examples.

Ancient Chinese educator and philosopher Confucius (551 - 479 BC) said that “If a man keeps cherishing his old knowledge, so as continually to be acquiring new, he may be a teacher of others.” Reviewing the old materials again and again helps students understand calculus deeper and use calculus to solve their problems in advanced courses and careers.

The Master also said, “Learning without thought is labor lost.” The traditional calculus series allowed little chance for students to think because they were burdened with unnecessary details, such as limits, continuity, partial fractions, trig substitutions, and Riemann sum. Consequently, few students remembered the ideas of Green’s theorem or divergence theorem a year after finishing Calculus III. What a significant waste of young people’s time, effort, and stress.

In traditional calculus curricula, students and instructors are so distracted by the tedious algebra procedures that they forget about their original goals of learning calculus. The iCal series always keeps the students engaged with their original goals of learning calculus to solve real-life problems and to help with their careers. This way avoids the no-purpose classes.

Learning calculus is not a competition of algebra skills. Instead, it is acquiring a new set of ideas and methods to solve problems that cannot be solved by algebra and trigonometry. iCal I, II, and III series not only cover all the core materials of the traditional Cal I, II, and III series, but also include some modern materials to support today’s digital economy. The modern materials, such as the Monte Carlo method for n-dimensional integrals, are introduced using an intuitive approach based on common sense and real-world examples. We will avoid using complicated algebra or trigonometry as much as we can.

With the above, we see that calculus is relevant to our daily life from the point of view of physics. We can even claim that “calculus is with us everyday.” When you walk, each step may be regarded as a differential, i.e., a cut, or called infinitesimal, and the total distance you have walked in a day is an integral of the differentials, i.e., a sum of all the steps. When you drive, your speedometer is derivative, and your odometer is integral of your speedometer. The data of your speedometer and odometer vary with time, i.e., as a function of time. When driving on a winding road, you think and do the following: How fast and in what direction is your car moving (i.e., the velocity), are you pushing gas or brake (i.e., the acceleration for changing speed for faster or slower), how fast are you turning your steering wheel (i.e., the curvature of the road, or what is the winding level of the road, some highly winding road has a yellow warning sign with a black curve on it!), and finally how long have you driven on this winding road (i.e., the length of a road, or illustrated as the length of a curve represented by a parametric function r(t))? These are some common calculus questions on a curve.

Similarly, you can ask some common questions on a surface related to our daily lives. How to quickly find the area of your grandma’s farm using a GPS planimeter App on your phone? What is the highest spot on a mountain surface? How to find the volume inside a closed surface, such as the volume of a potato inside its skin, or your body volume inside your skin? How to find the area of your T-shirt? How much body heat is lost through your T-shirt from 9 AM to 9 PM? How to find the cross-section area of your waist while easily measuring the perimeter of your waist? Or the other way around, if you know the volume of a 3D body, can you find the surface area of the body?

These daily life examples are all objects of calculus studies. These examples can of course be extended to engineering, science, business, and almost every field of quantitative studies. The method is always cutting and adding, described by functions, sum, and average related to differentials and integrals. Most computing of calculus in the real world cannot be done by hand. A computer must be used.

For computing, this book uses computer programming languages R and Python, which are free and can help students find well-paid jobs, particularly as data scientists. Many useful R and Python codes for graphics and computing are included in the book. For example, we have an R code to sing the song of Jingle Bells, and another to plot a fancy arts work based on two equations with time as a parameter, in addition to the R and Python codes for direct engineering and science applications.

R code can be developed and run in the RStudio interface. You can install R and RStudio in your computer following a Google search for instructions. The installation takes less than ten minutes.

Python code can be developed and run using the interface of Jupyter Notebook via Anaconda or Colab via Google. Again you can install Anaconda following a Google search. Colab does not need any installation if you have a Google account.

When using this book as a text, students are required to take their laptop computer to the classroom. Most formulas for definitions and theorems are provided with R and Python examples. Students can use the R or Python code to reproduce or modify the figures in the book. This unique feature of student-text interaction is new in the calculus textbook market. The feature supports the pedagogy of learning-by-doing, a progressive education philosophy in America largely attributed to John Dewey (1859 - 1952), an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. Confucius said that “I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.” iCal allows students to “do” calculus so that they can understand calculus. The “do” is carried out by quantitatively solving real-world problems with calculus methods, as well as numerical, graphic and symbolic computing. This is in a sharp contrast to the traditional calculus that stops at the symbolic solutions and rarely uses real-world data, numerical computing, and graphics plotting. iCal tells a complete story from the problem statement, calculus formula- tion setup, some limited formula handling, numerical and graphic solutions, and solution interpretation that answers the questions in the problem statement. This is basically a process of mathematical modeling. You may also regard the iCal approach as an extension of the common-core pedagogy of mathematics learning from K - 12 to college (i.e., 13 - 17).

The author of this iCal book has taught calculus over 20 times since 1987 at different universities in the United States, Canada, and China. The book is based on his experience of teaching and research. The first version of this text was written in 2021 for a summer course of Cal III at San Diego State University (SDSU).

He is deeply indebted to the students’ feedback and suggestions. He also appreciates discussions on calculus teaching with his colleagues and collaborators from around the world. He continues to improve the text and provide new versions. The second version was developed for the Spring semester Cal III in 2022 at SDSU. This is Version 8 for the summer session at SDSU in 2024.

Samuel S. P. Shen San Diego, California, USA

References

Fishbane, P.M., Gasiorowicz, S. and Thornton, S.T., 2005. Physics for Scientists and Engineers. 3rd edition, Pearson Prentice Hall, 1,232pp (6.0lb).

Holm, T., and K. Saxe, 2016: A common vision for undergraduate mathematics. Notices of the American. Mathematical Society. Vol. 63, No. 6, 630-634.

Knight, R.D., 2016. Physics for scientists and engineers: a strategic approach with modern physics. 4th edition, Pearson, 1,328pp (6.3lb).

Page, E., S.S.P. Shen, and R.C.J. Somerville, 2024: Can we do better at teaching mathematics to undergraduate atmospheric science students? Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS- D-22-0245.1

Saxe, K., L, Braddy, J. Bailer, R. Farinelli, T. Holm, and V. Mesa, 2015: A common vision for undergraduate mathematical sciences programs in 2025. The Mathematical Association of America, 73 pp.